Ancient Egypt Religion, Gods, goddesses, priests and Priestesses

The Ancient Egyptians are perhaps best known for their complex religion, whose hundreds of ancient Egyptians gods were worshiped in some of the most spectacular temples ever built.

As early as 17,000 BCE, carvings of wild cattle alongside strange hybrid creatures at the site of Qurta in southern Egypt suggest an early belief in the hidden forces of nature.

With Egypt’s earliest stone sculpture at about 7,000 years old believed to represent a cow, it is clear this was an animal that played an important role in the lives of the early Egyptians.

So too did their desert environment, in which the dominant Sun was worshiped as a variety of gods, much like the River Nile, whose annual life-bringing floodwaters were likewise venerated as divine.

As these aspects of the natural world gradually developed into individual gods, each region of Egypt also had their own local deities whose characters evolved through stories and myths.

One of the key myths for the Ancient Egyptian people was the Story of Creation, when the primeval waters of chaos receded to reveal a mound of earth on which life first appeared.

Yet with so many different deities throughout the Nile Valley, each region claimed that life had been created by their own local god.

In Egypt’s earliest capital, Memphis, their chief deity Ptah had emerged from the waters to summon up all living things by simply speaking their names, while at the nearby city of Sais, creation was regarded as the handiwork of the goddess Neith.

At Hermopolis, life had been sparked into being through the combined energies of eight gods, four male frogs and four female snakes, while in the far south at Aswan, the ram-headed god Khnum had created all life on his potter’s wheel.

But the most important creation myth centred on Heliopolis, where the supreme deity was the Sun god Ra.

Worshiped as ‘the Mother and Father of All’, the Sun produced twin children Tefnut, goddess of moisture, and Shu, god of air, who in turn produced the sky goddess Nut and the earth god Geb, parents of twin couples Isis and Osiris, Seth and Nephthys.

With Isis and her brother Osiris claimed as Egypt’s first rulers, they were succeeded by their son Horus, then the ‘Followers of Horus’, demigods who preceded Egypt’s first human rulers, each of whom was regarded as the gods’ child.

Over the subsequent 3,500 years of pharaonic history (c. 3100 BCE–395), Egypt’s pantheon of deities continued to expand as more gods were introduced and some merged together, creating a complex and varied pattern of religion.

What are the main Egyptian gods?

Although almost 1,500 deities are known by name, many of them combining with each other and sharing characteristics, these are some of the main ones

RA

God of the sun

Ra was Egypt’s most important sun god, also known as Khepri when rising, Atum when setting and the Aten as the solar disc. As the main creator deity, Ra also produced twin gods Shu and Tefnut.

GEB

God of the Earth

As the grandson of Ra and the son Shu and Tefnut, green-skinned Geb represented the Earth and was usually shown reclining, stretched out beneath his sister-wife Nut.

NUT

Goddess of the sky

As granddaughter of Ra, Nut was the sky goddess whose star-spangled body formed the heavens, held above her brother Geb by their father Shu, god of air.

ISIS

Goddess of motherhood and magic

The daughter of Geb and Nut, Isis was the perfect mother who eventually became Egypt’s most important deity, ‘more clever than a million god’ and ‘more powerful than 1,000 soldiers’.

OSIRIS

God of resurrection and fertility

Isis’s brother-husband Osiris was killed by his brother Seth, only to be resurrected by Isis to become Lord of the Underworld and the god of new life and fertility.

HORUS

God of Kingship

When his father Osiris became Lord of the Underworld, Horus succeeded him as King on Earth, and became the god with whom every human pharaoh was then identified.

SETH

God storms and chaos

Represented as a composite mythical creature, Seth was a turbulent god who killed his brother Osiris, only to be defeated by Osiris’s son and avenger Horus, helped by Isis.

NEPHTHYS

Goddess of protection

As fourth child of Geb and Nut, Nephthys was partnered with her brother Seth, but most often accompanied her sister Isis as twin protectors of the king and of the dead.

PTAH

God of creation and craftsmen

Ptah was a creator god and patron of craftsmen whose temple at Memphis, known as the ‘House of Ptah’s Soul’-‘hut-ka-ptah’-is the origin of the word ‘Egypt’.

THOTH

God of learning and the moon

As the ibis-headed god of wisdom and patron of scribes, Thoth invented writing and brought knowledge to humans.

His curved beak represented the crescent moon, and his main cult centre was Hermopolis.

NEITH

Goddess of creation

As a primeval creator deity represented by her symbol of crossed arrows and shield, warlike Neith, ‘Mistress of the Bow’, was worshiped at her cult centre Sais in the Delta.

AMUN

God of Thebes

Initially the local god of Thebes, whose name means ‘the hidden one’, Amun was combined with the sun god Ra to become Amun-Ra, king of the gods and Egypt’s state deity.

HATHOR

Goddess of love, beauty and motherhood

Often represented as a cow or a woman with cow ears, Hathor symbolized pleasure and joy and as a nurturing deity protected both the living and the dead.

SEKHMET

Goddess of destruction

The lioness goddess Sekhmet controlled the forces of destruction and was the protector of the king in battle. Her smaller, more kindly form was Bastet the cat goddess, protector of the home.

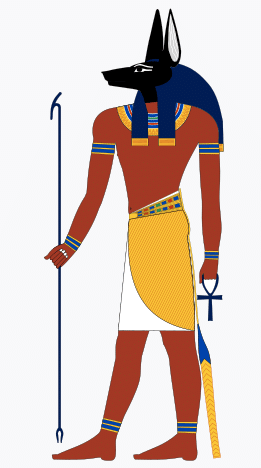

ANUBIS

God of embalming and the dead

The black jackal god Anubis was the guardian of cemeteries and god of embalming, who helped judge the dead before leading their souls into the afterlife.

TAWERET

Goddess of the home and childbirth

Taweret was a knife-wielding hippopotamus goddess who guarded at home, a protector of women and children who was invoked during childbirth to scare away evil forces.

BES

God of the home and childbirth

Bes was a dwarf-like god of the household who protected women and children alongside Taweret, like her carrying knives for protection, in his case he carried musical instruments for pleasure.

MA'AT

Goddess of truth and justice

As the deity who kept the universe in balance, Ma'at’s symbol was an ostrich feather against which the hearts of the dead were weighed and judged in order to achieve eternal life.

Ancient Egypt: temples of the gods

The Egyptians built temples as homes for their gods, believing their spirits resided inside their statues to which a constant stream of offerings were presented.

As early as c. 3500 BCE, the Egyptians built temples for their gods. Initially made of wood and reeds, these soon became permanent structures of stone that formed the centre of almost every settlement throughout the Nile Valley.

Evolving over time into ever more elaborate structures, the Egyptians aligned their temples to their environment, to the cardinal points, and to the movement of the Sun and stars.

Each temple’s sacred space was also enclosed by a huge exterior wall of mud-brick, within which the temple itself was made up of a series of successive stone-built shrines and courtyards.

Accessed through pylon-shaped gateways once flanked by tall cedar wood flag poles and secured by huge cedar wood doors, the temple walls were covered in brightly painted scenes of gods and kings, and like their floors and ceilings, often inlaid with precious metals and gemstones.

Then, to heighten the sense of reverence, the temple layout became progressively smaller and darker until reaching the innermost sanctuary, which housed the gods’ cult statues.

These were believed to contain the gods’ spirits, before which daily rituals were performed to maintain the divine presence and satisfy the gods who would in turn protect Egypt.

With the gods in residence, the temples became storehouses of divine power that could then be redirected through rituals for the benefit of the country.

To keep these sacred spaces ritually pure, only royalty and designated clergy were allowed inside – the majority of people were confined to the temple’s outer areas, where the main administrative buildings were located.

For Egypt’s temple complexes were not only religious centers, but their outer precincts a combination of town hall, library, university, medical center and law court – places where people came together for the purposes of community life at the heart of which lay the spirits of the very gods themselves.

What did ancient Egyptians celebrate?

The ancient Egyptian festival calendar

The Opening of the Year

(New Year’s Day)

Month 1, day 1 (19 July)

The Egyptian New Year began with the start of the annual Nile flood, which brought water to the desert landscape and allowed crops to grow.

With the floodwaters repeating the moment of creation, it was a time of national rejoicing when hymns claimed ‘the whole land leaps for joy’ and people threw flowers, offerings and even themselves into the water.

Opet Festival

Month 2, days 15-26

(September)

The Opet Festival began as an 11-day event when the cult statue of Amun was taken out of Karnak, accompanied by musicians, dancers, soldiers and the public.

The procession traveled five kilometers south to the temple of Luxor, where the god’s statue was joined by the pharaoh in secret ceremonies designed to replenish royal power, amidst feasting and rejoicing.

The Festival of Khoiak

Month 4, days 18-30

(November)

The Festival of Khoiak celebrated the life, death and resurrection of Osiris.

Since this was based on the agricultural cycle in which the crops cut down were grown again, ceremonies included planting seeds in Osiris-shaped containers.

It was celebrated when the Nile floodwaters were receding, leaving rich, black sediment on the riverbanks into which new crops were planted.

Festival of Bastet

Month 8, days 4-5

The cat goddess, Bastet, was closely linked to the lioness Sekhmet and cowlike Hathor, these deities’ lively worship involving much singing, dancing and drinking – all key elements of Bastet’s annual fertility festival. Boatloads of men and women would arrive at her cult centre Bubastis to celebrate, when it was reported that ‘more wine is drunk at this feast than in the whole year’.

Festival of the Valley

New Moon, Month 10

At the annual Festival of the Valley, the cult statue of Amun was taken out from Karnak and across the Nile to Thebes’s west bank.

While it was here, the statue visited the tombs and temples of the previous kings that were buried there, accompanied by the local population, who would also visit the tombs of their own relatives to feast with their spirits and leave them offerings.

Festival of the Beautiful

Meeting

New Moon, Month 11

This festival celebrated the marriage between the god Horus of Edfu and goddess Hathor of Dendera.

Beginning 14 days before the new moon, Hathor’s cult statue was transported 70 kilometres south to Edfu temple, where it was placed beside the statue of Horus.

14 more days of festivities involved the participation of the royal family alongside the general population.

What were priests in ancient Egypt?

Ancient Egypt’s priests were known as ‘servants of god’, who carried out religious rites before the gods’ statues instead of a human congregation

Each successive pharaoh was regarded as a child of the gods, and as the gods’ representative on Earth, was also the supreme high priest of every temple.

However, with so many different temples throughout Egypt, the pharaoh’s duties had to be delegated to each temple’s high priest, who was often a royal relative selected by the king to guarantee their loyalty.

Within large temples like Karnak or Memphis, the power of the priests was considerable, since the temples owned much land and the temple treasuries were very wealthy.

The priests also controlled the gods’ cult statues, which functioned as oracles, whose pronouncements were interpreted by the priests, and could pass judgment in legal cases and even influence royal succession.

At times when the crown was weak, the high priests’ powers became so great that some took on additional roles as military generals, whose struggles with the monarchy could lead to civil war.

Yet most of the time the priests carried out their role, helping the king maintain strong relations with the gods whose spirits were believed to dwell within their cult statues.

Housed in the sanctuary at the innermost part of the temple, it was here that the high priest led daily rites, assisted by a staff of male and female clergy, from the ‘god’s wife’ priestess to the deputy high priest who oversaw supplies of offerings and the temple scribes who kept accounts and composed ritual texts.

There were also lector priests who read out these texts, temple astronomers or ‘hour priests’ who calculated the correct timings for rituals, and temple dancers, singers and musicians who entertained the gods and impersonated them in ritual dramas wearing masks and costumes.

Other staff included the temple gardeners, brewers, bakers and butchers who supplied the daily offerings, the temple weavers, jewellers, barbers and wig makers who supplied both the gods and their clergy, and the numerous craftsmen, carpenters and builders who undertook building work, carried out repairs and kept the temples in good order.

In fact so numerous were such personnel that eventually well over 100,000 people were employed in the upkeep of Egypt’s three main temples of Karnak, Memphis and Heliopolis.

What did priestesses do in ancient Egypt?

Women were priestesses to both goddesses and gods, undertaking similar roles to their male counterparts and receiving the same pay.

The most common priestess title was ‘chantress’, with some women impersonating goddesses in rituals and the wives of high priests holding the title ‘leader of the musical troupe’.

Although most high priests were men, as were the lector priests who read out sacred texts, women held both these offices at times.

Yet the most important priestess was the ‘God’s Wife’, a title held by a succession of royal women acting as the human consort of the god Amun at Karnak.

The God’s Wife led sacred processions with the king or his deputy the high priest, and like them could enter the innermost shrine to make offerings keeping the gods content.

She also took an active role in defending Egypt by magical means, shooting arrows into ritual targets and burning images of enemies.

As the role brought great wealth and prestige, kings appointed their sisters or daughters as God’s Wife to enhance their own status, and eventually regarded as the equivalent of a king shown with kingly scepters, these women could delegate on the king’s behalf, both within the temple and in matters of state.

Comments

Post a Comment